Kenji Morimoto’s Family Had Not One, But Two, Slaw Recipes

Who are you, what do you do and where are you really from?

Kenji Morimoto. I am a fourth generation Japanese American, born and raised in Chicago and live in London. I dabble in many things but spend the majority of my time working in finance and food, the latter focused on fermentation and connecting the dots between diasporic traditions. I explore this through content creation (@kenjcooks), recipe development, fermentation workshops and supper clubs.

My name is Kenji, both a family name, as well as chosen due to its ability to be shortened to a Western name, a vehicle for assimilation. I am a product of my community and my family's history:

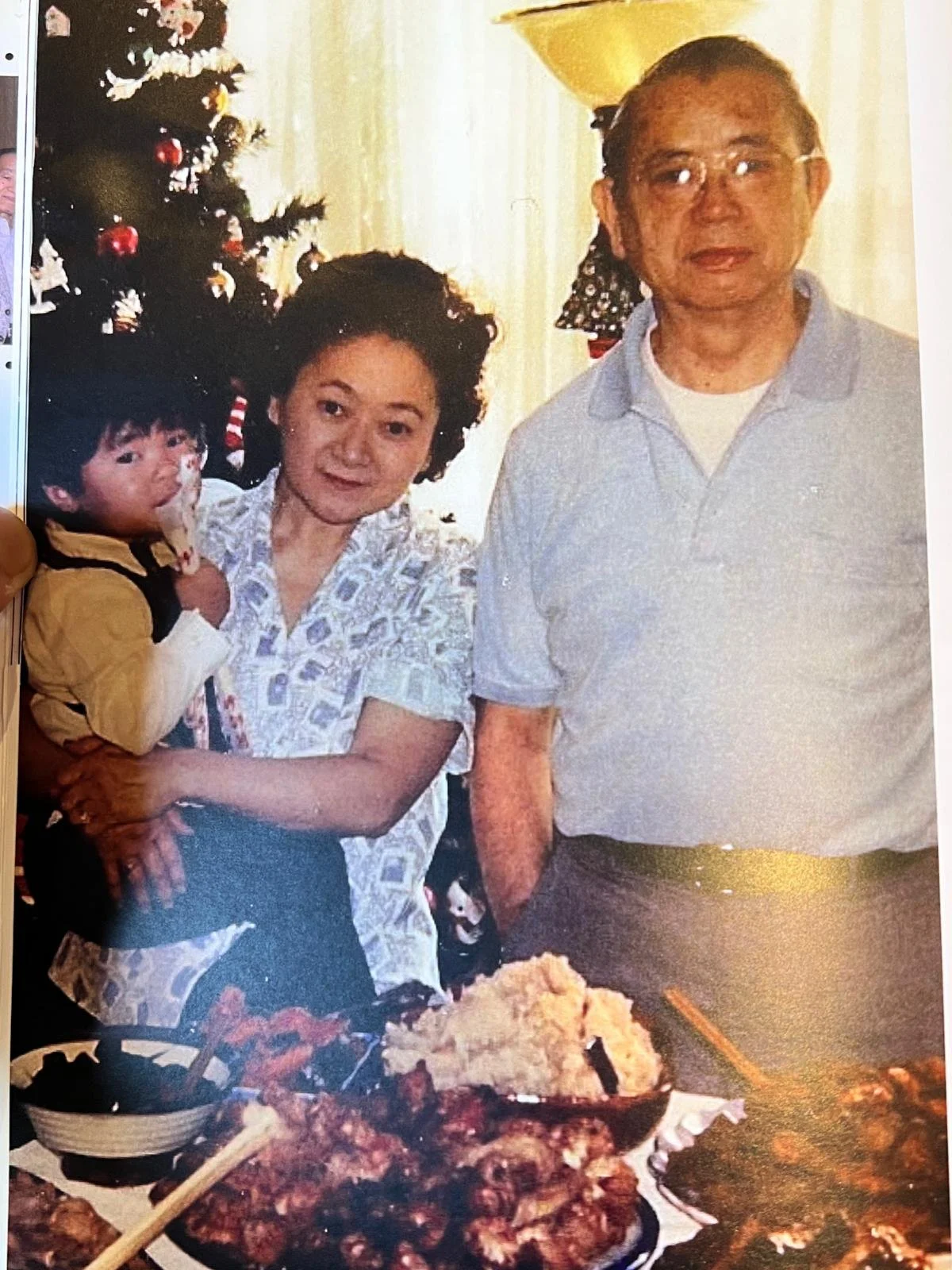

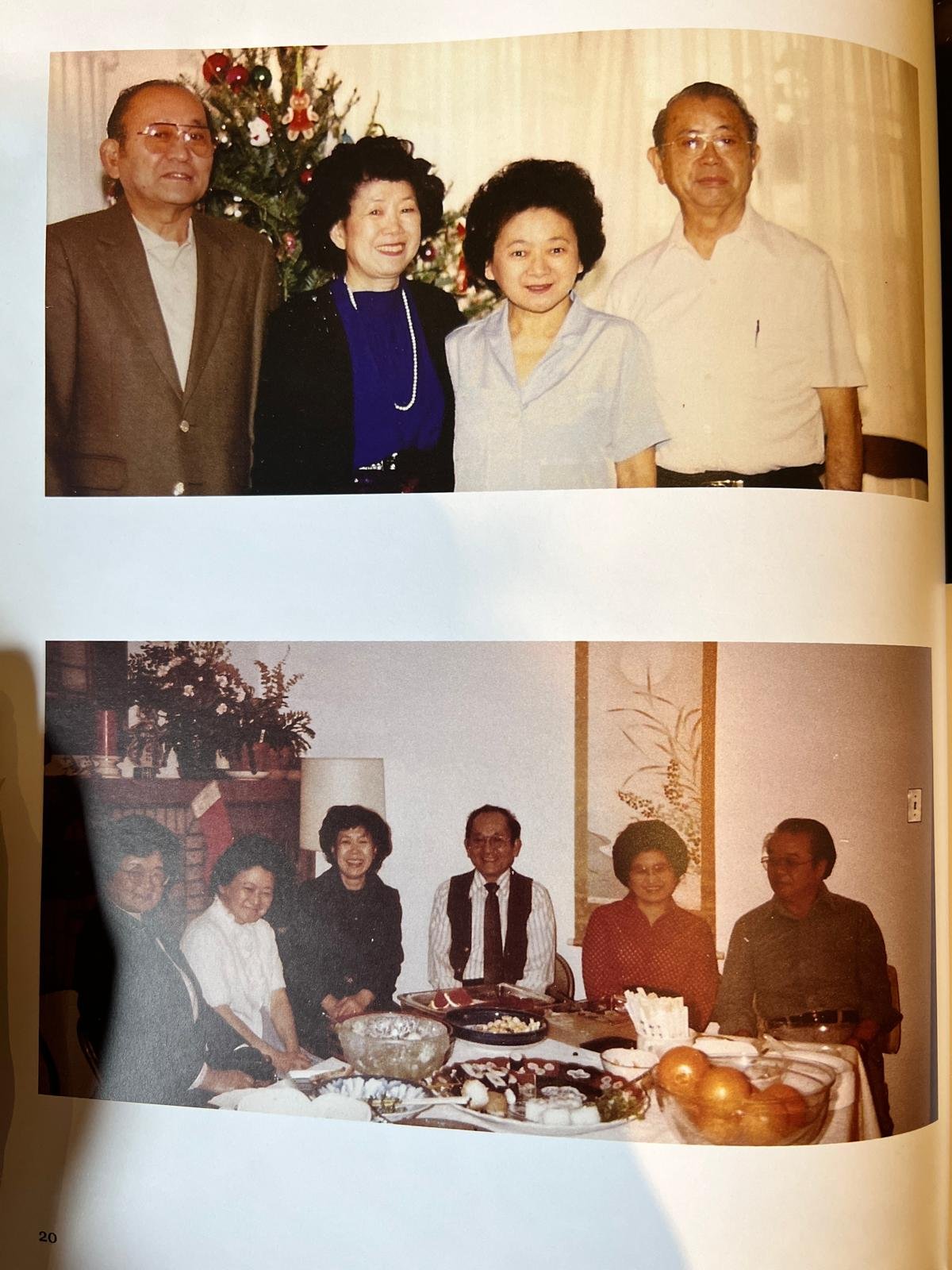

Chicago is where my parents were born, ceremony and society centred on rebuilding a Japanese American community in the aftermath of WWII internment.

LA Little Tokyo and SF Japantown is where my grandparents were born, bustling centres of commerce with the hope of the American dream - the lived experience for both my American grandparents and their immigrants parents.

Hiroshima is where all eight of my great grandparents were born, escaping poverty and famine in the late 1800s before working in sugar plantations in Hawaii and on the Transcontinental Railroad, others sent as picture brides and working as maids.

But I’m really from Japan.

Any thoughts on ‘Asian slaw’?

Growing up, my family often had two varieties of what would be considered ‘Asian slaw’ at our dinner table.

The first was my great auntie Fumi’s Napa salad, chopped Napa cabbage (or Chinese leaf) dressed with a sweet soy sauce and sesame oil dressing and garnished with fried chow mein noodles, green onion and toasted sesame seeds. This dish was her contribution to most family potlucks, with clear Chinese influences. A taste for Chinese (and specifically Cantonese) flavours run deep in my community as Chinese restaurants and banquet halls were the location of choice for celebration for my grandparents and parents during the 1950s-1970s. The second was a ‘Chinese chicken salad’, made by Ron, a half Chinese/half Japanese Hawaiian who was my uncle’s roommate during university and is now part of the family. Similar flavour profile but used thinly sliced white cabbage, crumbled instant ramen noodles, and shredded teriyaki chicken. What I loved (and continue to love) about these two dishes is what they reflect, a confluence of cultures as well as how food evolves due to location and people.

I never considered either of these ‘slaws’ until I grew older as the popularity of ‘Pan-Asian’ cuisine grew and variations were used as a side to, well, everything: from curries to garnishing sticky glazed katsu burgers. I remember experiencing a tinge of guilt when I realised my favourite order at my family’s go-to lunch takeout restaurant was ‘Asian Chicken Salad’. Did it legitimise this pan-Asian and arguably confused ‘Asian’ salad that my Japanese American family ordered this? Does this even matter? It wasn't nearly as good as my family’s versions, but nostalgia is powerful and it does tick that ‘Asian American’ all inclusive box sometimes.

Eaten any memorable slaws, Asian or otherwise?

It may be a controversial opinion but I’d argue that many varieties of tsukemono, or Japanese pickled vegetables, could be considered a slaw - a variety of vegetables, often including cabbage, salted and brined to create a crunchy accompaniment to a meal. Whilst there’s of course a great diversity within the umbrella of tsukemono, many of the methods are similar, regardless of the type - be it asazuke, shoyuzuke, or misozuke.

My Buddhist temple was the best place to try out homemade tsukemono as every community gathering was a potluck with each family contributing a dish to share - from homemade makizushi to pickles. In many ways, this is what first showed me the variation in tsukemono’s family traditions even in my own community alone: the sweet bite of a pickled rakkyo onion, the Hawaiian influences in sanbaizuke, and the magic of kombu in both umami and texture. What I gravitated to immediately was this shoyu based cabbage and cucumber tsukemono made by a Nisei (second generation Japanese American) woman, who was close friends with my maternal grandparents from the camps. To me, it was quintessentially Japanese American: a bit sweeter than the tsukemono you'd get in Japan and using more accessible produce (white cabbage and Persian cucumbers). I’d have a ritual as a child of skipping to the front of the food table and grabbing a rice ball and tsukemono before sitting with my grandparents on foldable chairs as they swapped stories in a hybrid Japanese English.

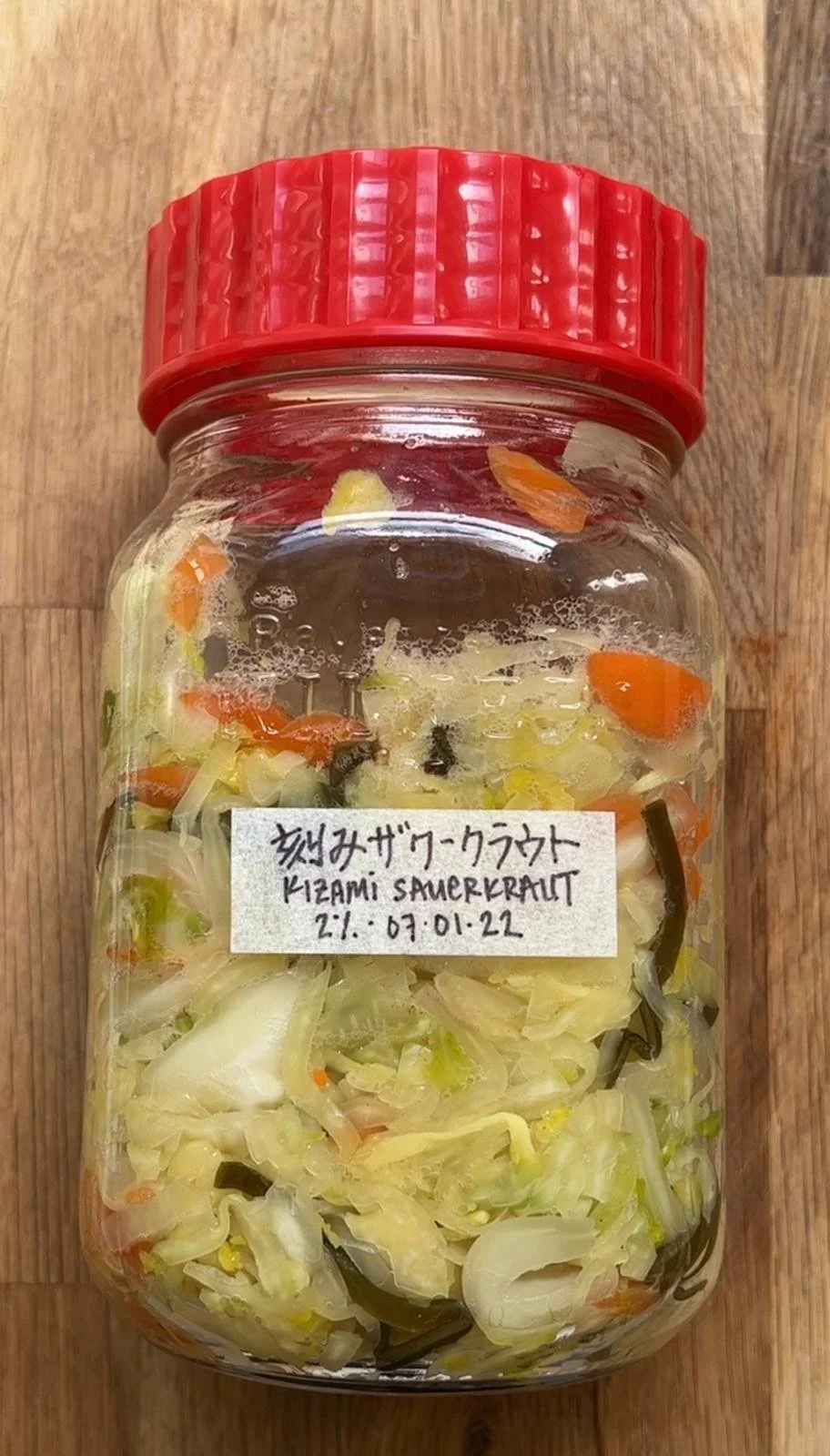

Kizami Cabbage Tsukemono

“Kenji, be sure to buy kizami tsukemono!” my grandmother would often remind me. It was her favourite, a simple combination of thinly sliced cabbage, carrot, mustard greens - all salted and flavoured with kombu seaweed, chilli flakes, and ginger. Vacuum packed and sent from Japan.

For Oshougatsu (Japanese New Year), my mom and I often did all of the shopping; a visit to a minimum of three Asian/Japanese grocery stores in the suburbs of Chicago to pick up the necessary ingredients to cook up my family’s most important feast to welcome the new year. At first, the greater majority of tsukemono were store bought but as I grew older and got more involved in pickling and fermentation, I ended up making the majority of the pickles. Kizami was the one I felt the most urgency to make - and perfect - as it was my grandmother's favourite and the one my grandparents always said reminded them most of nihon no aji or the Japanese flavour.

Less than a recipe, there’s a specific process that should be followed: vegetables should be thinly sliced and salted with 2% salt; a weight or fermentation press will allow for a consistent pickling process. After a minimum of an hour, add thinly sliced kombu, shredded ginger, and cut red chilli pepper, and add this to vegetables once the excess water has been removed. At this point, I like to put it all in a plastic bag and remove the air to ensure the vegetables absorb the flavour. The flavour will of course intensify over time but I'd say you’re in a good position after 45 minutes.

These should last in the fridge for up to a week if kept in an airtight container. You can eat it as is, or further dress them with some shoyu, katsuobushi (shaved bonito flakes) or toasted sesame seeds.

Tell me about the ingredients and why you chose them for this recipe.

There’s nothing special about the ingredients. They’re all humble, accessible, and in my opinion, that is what makes this method so special. With a bit of love and attention, you can transform the vegetables’ textures and add a great side to any meal. However this recipe’s versatility is what I like to celebrate. Use whatever you have: Napa cabbage, Japanese cucumber, mustard greens, and daikon radish are traditional. But why not try white cabbage? English cucumbers or radishes? Fennel? Celery?

How will you serve your slaw?

My grandmother's fried chicken, onigiri (rice balls) filled with tsukudani or umeboshi, cans of Diet Coke.

Who will you invite to eat your slaw?

My four grandparents. They taught me an immense amount about resilience, family, and the role food plays as a cultural driver within one’s identity. They were constantly in search of the nostalgic flavours of home throughout their life: from their time in internment camps during WWII where they had limited access to Japanese food, to creating their own traditions with their families in white majority communities after the war, to seeing what they craved and wanted for as they moved to assisted living homes and their memories faded due to dementia. It would be the greatest honour to cook for them and share a dinner table with them again.