Anna Ansari Time Travels With Kalam Polo

(This interview was transcribed and edited)

Who are you, what do you do and what do you say if people have ever asked you where you really come from?

I am Anna Ansari, a former customs and international trade attorney. Also a former Chinese history scholar. I say former because I’m not working as either, though they’re both ticking around in my brain. I finished my proposal for a book that traces the different origins of food flavours and dishes across the Silk Road. I spent a lot of my youth in Beijing and Shanghai where I first discovered Uyghur food, and it opened up my taste-mind, because my father is Turkish Iranian.

Which brings me to your question about where I’m really from. It’s funny because I’ve been in the UK for 10 years now, and I very clearly say that I’m from America, from the Midwest and New York for a long time. But when I was growing up in my 20s and 30s, people in the US would say, ‘Oh I’m sorry, where are you from?’ They meant, what kind of a name is that? It’s not your typical Smith or Johnson. I’d say, ‘Oh, my dad’s from Iran’. ‘Oh, he’s an Arab.’ And then it would draw these looks of fear, because Iran in the US has a much more negative connotation than in the UK as a result of the Contra Affair and the early 80s crisis. Because it was a politically fraught term I grew up not loving to say that I was Iranian. And some people didn’t like to have little Iranian kids come over to sleepovers and excluded my sister and me from bar and bat mitzvahs.

Now that I’m in the UK, it’s clear that I’m American. It’s a distinct identity. I might be the most American person I know; my mom is American, born and raised in Michigan. Her family has English and German roots. Her English side arrived on the Mayflower from Plymouth. My great-grandfather, several generations back, was the governor of Plymouth Colony. On her German side, they came from Bavaria in the late 1800s and settled in New York. They went through Ellis Island and eventually opened a bakery on the Lower East Side. So, I have this combination of Mayflower and Ellis Island in my heritage. And, because of my father, I’m a first-generation immigrant. Like I said, I’m the most American person I know.

Long answer.

But I love those long backstories where you have to go a few generations back and first answer by telling the story of your parents and how they came to this country. I don’t think our parents necessarily were able to tell those stories.

No. I don’t think my mom thought much about where she was from or her backstory. My younger sister looked up all the history and found out about the immigrants to Ellis Island. She was like, this is crazy! How come you never taught us about this? My dad likes to tell people he’s from Michigan and they kind of look at him like, what are we supposed to say now? A man with an accent is telling us he’s from one of the largest African-American cities in the US. He’s like, ‘I’m from Detroit’. And I feel like because I’m [perceived as] a white person, no one is questioning me. If you have an outwardly assimilating look, the questions stop.

You’re what they would say is white passing.

I encountered you via Cook For Iran and I’m interested in how you use food to navigate and negotiate your Iranian identity. Is that a way to present your Iranian-ness? Can you tell me about that journey?

It started with moving here, which really made me think about my identity both as a white American and as an Iranian American, because I’m so clearly not a white British person. I would have people ask me, ‘what do “your people” do for holidays?’ I would think to myself, who are you asking about? Me? As an American? Or the Iranian side? Like, who do you think my people are?

So I started thinking, who am I? Which is something I truly had not thought about until I moved to the UK. I just started cooking more during lockdown. It drove home how I wanted to spend these three meals a day cooking for my son and husband. I kept returning to the comforts of Iranian food. And when I couldn’t be with my family in the US I would be with them through these food memories. I’d just send videos to my dad or my siblings or cousins, and they’d be like, ‘we’re gonna do that too!’ So it’s a way of connecting both to that food heritage as well as to my family and bringing it into my current family. My son loves Persian food now and I love that he loves that.

I started writing more about the connections I have with food, food memories and how they traverse time and place through immigration. The movement of goods and people also includes the movement of these flavour memories and ingredients, and things change. But that doesn’t mean they lose any of their meaning to the person who is transporting them. It’s basically how I’m teaching my son, the same way my father passed on culinary ingredients and dishes to me.

Cook For Iran came around. Layla Yarjani and Gemma Bell have done such a great job with it, and I was so excited to contribute. They did an open call for city leads; so now I’m a volunteer London community lead, raising money for the California-based Center for Mind-Body Medicine, which has practitioners across the globe. Our money goes to this charity, who then funnels it into the Iranian practitioners that help people dealing with trauma because of the current situation in Iran.

To raise money we’re raising cultural and political awareness through food, like with my pop-up dinners here in Walthamstow. It’s super community based, where I can talk to the diners about Iran, my family’s history and the individual dishes. I lived in West London for the first three years, where there are a lot more Iranian restaurants. Over here in Walthamstow - not so much. It’s a predominantly Pakistani neighbourhood. But Pakistan and Iran have been buddies. So the neighbourhood is really supportive and I’ve been really pleased to share my heritage and cooking with strangers and neighbours.

These food memories you mentioned - when you were young did your father cook for you? Did he teach you about Iranian food and culture or did you have to go on that journey yourself?

Culture, yes. My father is almost 87 years old, a retired heart and lung surgeon. When I was growing up he was extraordinarily busy. I remember him getting up from the dinner table at Christmas to go and perform surgery. As a result I never learned Turkish Azeri - his mother tongue - or Farsi. It was challenging when we’d go to all these cultural events because I didn’t know what the heck was going on. But frankly there were a lot of white American wives with kids like us too. We grew up spending a lot of time at these parties and barbecues with poetry readings for hours where I didn’t know what anyone was saying, but we’d just sit in the corner watching Aladdin. Like, that’s our culture too! But I was always surrounded by different languages.

We always had big parties for Nowruz, Persian New Year. Every year we’d set up a big haft seen, which is a table with all these symbolic elements on it. We also did Christmas and Thanksgiving and Fourth of July, but food wise, my dad was not a cook. If given the opportunity my dad will eat fresh fruit, nuts, cheese and bread. We go to his house now and there’s nothing except nuts and berries. When he would visit me in college - before there were any good Iranian restaurants in New York - we just went to Chinese restaurants because he wanted rice with every meal.

Anna’s great aunt Khalejan

My great aunt came over from Iran and stayed with us for a while before I was born. She taught my mom how to cook Iranian food without speaking English. She would just show her what to do, what spices, when to put them in, when to take things off the oven or stove, how everything should taste. We also had a very good family friend who’s now passed away; my dad’s best friend who was known as the ‘barbecue king’. He was in charge of all the kebabs every summer. Those are my food memories: my mom cooking Iranian food and my father’s friend, Dr. Frugh, making incredible kebabs. I actually contributed to Olia Hercules’ most recent book, Home Food, with a vignette about eating Dr Frugh’s koobideh in suburban Michigan in the 90s.

I do think that not speaking the language for me means I’ve been able to purposefully connect to my heritage through food. My older sister and brother speak Farsi and Turkish fluently but they cannot cook a pot of rice to save their lives. And they really don’t care. For me it’s partially because of the lack of language that I’ve been able to connect to that side of myself and I want to pass that down to my son.

I see that a lot in the diaspora community. The almost obsession with food is trying to hold onto something, and I think that if we had that linguistic fluency we wouldn’t be so attached?

Well, you already have that connection so you don’t need to make it on any other plane, but I’ve got nothing else. I mean, I can sit down and read the Shahnameh or Ferdowsi in translation, but all these poets always lose something in translation. But I don’t lose so much in translation when I make a cabbage rice dish and send it to my dad and cousins, and everyone’s like, oh Anna, we don’t even make this anymore!

And that’s the validation you get from the family WhatsApp group!

I do think that with my older siblings who are full Iranian [from dad’s previous marriage], who can speak the language, whereas I’ve only been to Azerbaijan a number of times… They’re like, she might not speak the language, like you’re not really one of us, but look at what she’s doing over there - cooking for Iran, cooking Iranian food… I think being able to share this with my family - is this validation?

Can you explain about Azeri Turkish?

My dad is from outside of Tabriz, which was the capital of the northernmost province in Iran in the 1860s. There was a treaty with Russia where the area we now know as Azerbaijan was split, and half was given over to the Russian Empire. The other half was given over to the Persian Empire. So what is now the Republic of Azerbaijan was under Russian Empire rule, then Communist rule, and now, is its own separate republic since 1991. South Azerbaijan - which is not really a term that’s used that often - is still within the boundaries of the Islamic Republic of Iran. So my father grew up in this sort of weird land where he grew up speaking Azeri Turkish, but where now you’re not allowed to speak that - only Farsi. Because there’s been this movement to eradicate this Turkic language and identity and assimilate it into the Persian-ness of Iran.

So my father was very clear from the get go: I try to not say Persian food when I’m talking about Iranian food. It’s like saying ‘Han Chinese food’, right? It’s a very particular, meaning laden term that most people don’t even think about. I was taught that Iran is the country, Persia is a cultural ethnic word. Same with Turkish. As for Azeri, this old long forgotten part of Iran that is still there? Apparently two weeks ago, a big group of members of the Israeli parliament went to the foreign minister of Israel and asked for global assistance for the people of South Azerbaijan. The ayatollahs were not happy with it.

But when we go to Azerbaijan proper my dad can’t read anything because post-independence from the USSR the Azeri authorities embarked on this language building process, where they took some from Cyrillic, some from Roman. It’s a totally different language, whereas my dad can read Arabic - because Farsi and Turkish are written in Arabic as a result of Islam and the Quran being written in Arabic everywhere. But he very much does not consider himself Persian; we are Azeri from Iran.

And it’s not Persian New Year, it’s Iranian New Year!

It’s fascinating, because the language of identity politics and how language is being used as a form of supremacy or cultural eradication is so strong. I see it so obviously in overseas Chinese communities when we fight so much over labels and language. And even the way that food gets sucked into it - food language and dish origins. Even anglicised spellings. Wow, we get so worked up about this!

I sent my dad this essay from my book proposal, and I had referred to the crust at the bottom of rice as tahdig. Tahdig is the phrase that most people know, right? But it’s the Persian word and I have never used that word in my life. We call it qazmagh. But in the proposal I was like, if I write this, no one’s gonna know what I’m talking about. But this word tahdig hurts my ear, because of what has been drilled into me. So then you’ve got this conflict of what are we going to call these dishes?

I wrote to Delicious Magazine a couple of months ago because they did a thing on tahdig. I was so pleased to see it featured but whoever edited the article just referred to the whole dish as tahdig, and it just irked me so much. My husband was like, who cares - you should be happy that there’s an Iranian dish in there! But I was thinking that if this is how we’re going to get this cuisine into the mainstream and into people’s consciousness, I don’t want it to be incorrect. But then even tahdig to my family is incorrect. So there are all these layers of frustration and jubilation that this is even in a magazine, especially with the explosion of Iranian food and recipe writing in the past 10 years.

My mom bought this book when she was learning to cook Iranian food, called Food Of Life by Najmieh Batmanglij, which is the bible of Persian and Iranian cooking in the US - and to me it still is. Now that you can go online and google any Persian or Iranian recipe, and that there was a feature in Delicious Magazine going out all over the UK is great. But the fact that they can’t even get the dish right or check it is less great to me.

And what about our obsession with authenticity?

I find the UK to be curious because of empire and colonialism. At least in the US, frankly we’re just a big mix of people. Pizza is Italian, but then we talk about different regional varieties within the United States rather than do we really care where things are from? So this idea of origin and authenticity in the US, is diluted for better and for worse.

Anna’s great grandmother Alice

Great aunt Khalejan

On this topic, do you think that food - especially with Cook for Iran - can never be without politics, especially in diaspora discourse? Do you think it can be without that projection of people’s identities? Can we just enjoy it for what it is?

I think we can enjoy it for what it is. The first time I went to China and had Uyghur food, I never thought much about the politics of the people who were creating this food for me in these alleyways in Beijing or Kunming and why they were in these alleyways to begin with. And when they started disappearing, asking why that was. But it’s not because I had my head in the sand;I just didn’t connect the two. For a lot of people food doesn’t need to be political because you’re looking at it through your tastebuds. I don’t know if that’s a good thing - maybe you do want to be tasting these flavours and cuisines and thinking about why you can’t get Uyghur food pretty much outside of China. There’s like one restaurant in the entire United States. Why can’t that cuisine escape geopolitical boundaries? Because the people are not allowed to move, so the politics are deep in there.

So with Cook For Syria, Cook For Ukraine or Cook For Iran, you’re bringing politics into the food in a positive way. But when you get these fights over baklava between the Greeks and the Turks or over hummus between the Israelis and the Lebanese - which have gone on for ages! - you can’t take that out of it. Recently Dianne Jacob wrote into the New York Times about a recipe they had described as Israeli and she was like, Oh hell no. This is Iraqi Jewish. She wrote on her Substack about why she had to say something - she didn’t want her particular heritage to be lost in this political fray. If you’re Jewish they think you’re from the Middle East, but no one cares about the Iraqi Jews. And then for some people - if they read an Israeli recipe, maybe they wouldn’t want to cook it because they do have issues with that. Maybe they would be more interested if it did say Iraqi.

It’s interesting how we’re willing to dehumanise the people of certain political superpower countries - Israel is one, China is another. You don’t see the same with Iran, perhaps because Iranian people are leading this revolution. But I see Chinese people dehumanised a lot. Even without our community, people are trying to distance themselves from using ‘Chinese’ as a label. There’s this move towards ESEA (East and South East Asian), or if you’re from outside mainland China, you’re very clear to say ‘I’m a Hongkonger’ or Malaysian Chinese, Taiwanese. You see it in how we consume the culture too. Like when people don’t support Israel by not cooking Israel recipes, only Palestinian ones.

How do you make these differentiations? There is a time for politics and there’s a time for food, and there’s also a great time for them to mix but it doesn’t need to be full of conflict.

How did your time in China come about?

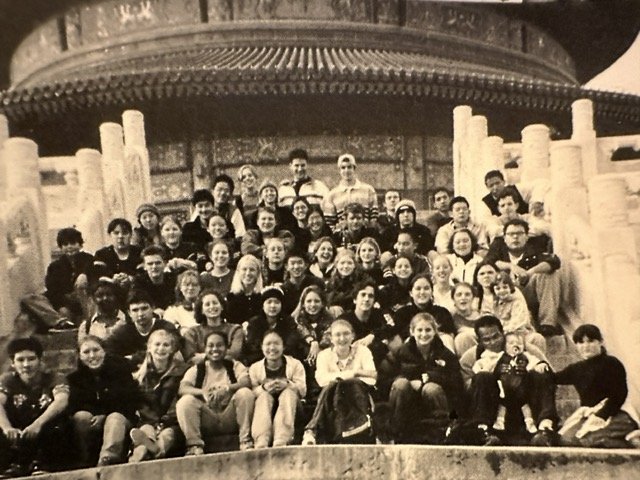

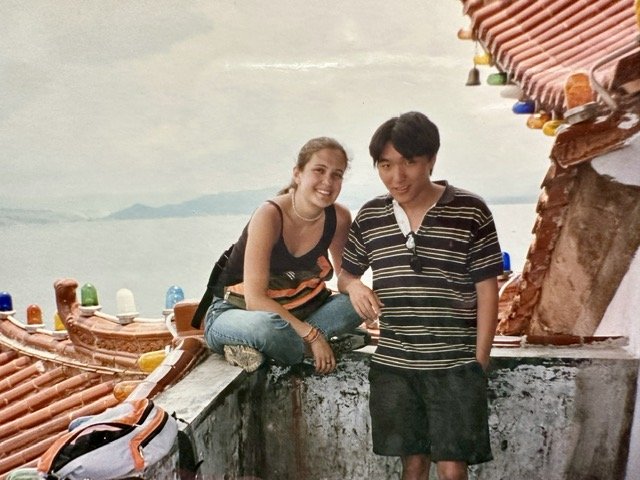

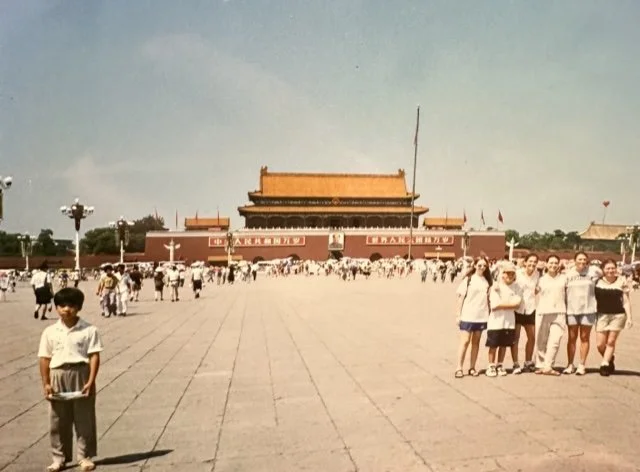

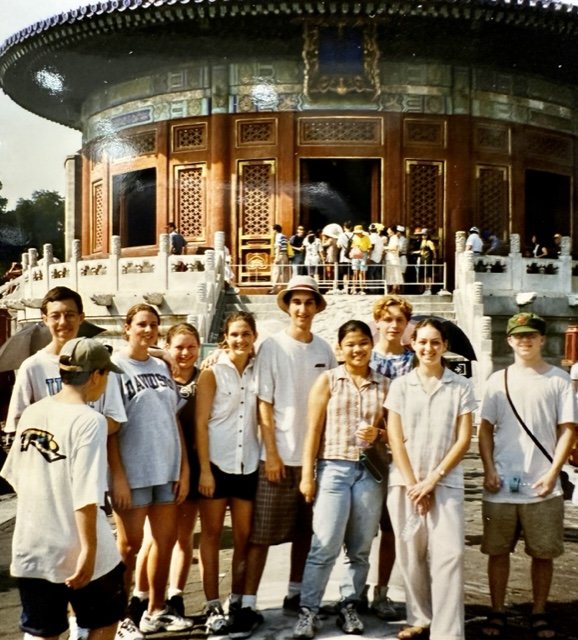

It was summer of ‘97. My dad sent me to China as a 15 year old. I’d been caught drinking and smoking the year before at a French programme in Switzerland, and they were like, you’re not going back to Europe with those loosey goosey Europeans. You’re gonna do something educational this summer. There was a Duke University programme and it was a decision between Japan or China. My father basically decided that China’s going to be important and interesting and where the future is at.

I spent two months in Shanghai - which included my 16th birthday and my first kiss. It was just totally mind-bogglingly different from what I was used to. I didn’t grow up in New York City, teeming with crowds, subways and cars and Chinatowns. I grew up in suburban Michigan, at a time when Detroit was not safe so we didn’t go downtown. So Shanghai was sensory overload in the best way possible, and I was besotted. After graduating high school I went to China on a programme and lived with a Chinese family in Beijing for a year. At the time I had been accepted to Barnard College, Columbia University, but I deferred for a year. My parents were so happy because - hilariously - they thought it was safer to send me across the world to live with strangers than go to NYC in the late ‘90s.

So I was in Beijing from August ‘98 through June ‘99, taking like 20 hours of language studies everyday. I had a host mother, father and sister and biked to school every day. It was very funny at Columbia, because they put me in Chinese class with Chinese Americans who never had formal language training, many of whom grew up in Flushing with great Chinese but couldn’t read or write. I walked into this class and they’re like, what are you doing here? Because I had this crazy strong Beijing accent with all the ‘r’s. My plan had been to study political science, but it just so happened that while I was at Columbia all the leading academics in Chinese and Japanese literature were there - like Paul Anderer, David Wang, William de Bary. So I did East Asian Studies with a concentration on Chinese literature. Then I did a masters in Chinese studies at Yale and moved back to China for a while, where I was taking teenage kids around China and teaching them about Chinese history; I did the same thing for New York City teachers while working for the China Institute in New York.

My path has been really meandering and in the past two years, since Cook For Iran and working on this book proposal, writing and getting to know myself through food, it has brought a lot of these different strands of my background together. Maybe going to China as a teenager wasn’t so I could become a Chinese historian or publish a paper on Chinese bankruptcy law, which I actually have done… Maybe it really was about going on that first bike ride down an alleyway and trying Uyghur food, realising that part of myself was there too - through that circular flavour experience that is validating at this point in life.

What were those flavours or ingredients that made you have that moment of realisation?

Lamb and cumin. I was like, wait a second. I’m coming from Midwest America where Chinese food is sweet and sour pork, moo shu and chop suey. And these [food vendors] had little hats on, darker skin and not almond-shaped eyes. I was like, who are these people and why does this taste like something I’ve had before without even knowing it? It was something I probably had at one of these lakeside gatherings in Michigan with my dad’s diasporic friends.

And then there were the breads. The first time I went to Baku, we had this bread that came out of the tandir oven, and it reminded me of all the Uyghur breads in Beijing. I was like, this is the same food! These people have gone across the same routes and that’s why you get breads that look the same in Uzbekistan, Xinjiang, Georgia and Armenia and Azerbaijan. I love it, it brings me a little bit of joy how connected people are, especially these days when there is so much more emphasis on how we are different, especially in the US.

Tribalism at its worst!

What do you think when you hear ‘Asian slaw’?

I had no reference point for Asian slaw. I think possibly the only place in the US I can really think of would be PF Chang’s or something, with some crispy wonton on top and a peanut dressing.

I’ve spoken to some people who know exactly what I’m talking about, and some who don’t. But once you hear about it, you’ll start noticing it. You’ll see ‘Asian salad’, ‘Asian slaw’, where Asian is a shorthand for something healthy that doesn’t have mayo, and lots of soy sauce, sesame seeds and peanuts.

What about cabbage itself?

I love cabbage but never thought much about it. I remember my host mom told me she was never eating cabbage again because she ate it during the Cultural Revolution. I didn’t like vegetables as a teen, but I love stir fried cabbage. And I love cabbage in hotpot and how it soaks up all the spice. But that was the extent of my cabbage knowledge. And I never cooked with it because I thought of it as something in American cuisine as coleslaw, dripping in mayonnaise without much flavour, this icky old cafeteria food.

During lockdown I started getting into cabbage because we subscribe to a vegetable delivery service and every week they sent another head of cabbage. Like, 10 potatoes and a cabbage. So I started playing around with cabbage and remembered this Iranian cabbage rice that my great aunt used to make. It’s so good and it connects me to home. Stuffed cabbage is not my favourite, but I liked it sauteed. I love doing it either in the oven or on the barbecue grill - a charred cabbage with compound anchovy butter. It’s an explosion of umami!

You can make this Iranian cabbage rice with either meatballs or sautéed ground meat. Personally, I prefer the ground meat, a preference that goes back to my great-grandmother in Michigan on my mom’s side. She wasn’t very well off and used to make us sautéed cabbage with ground beef, simply seasoned with salt and pepper.

There’s something about making this dish that resonates with me; when I sauté the cabbage and add the beef, along with spices like cinnamon, cardamom, rose petals, and other Iranian flavours, it brings back memories of my great-grandmother, who used to cook it for us when my parents were super busy. I don’t even think I liked it back then. It’s a completely different cabbage and beef dish [to kalam polo]. It brings me so much joy to make and eat because it holds deep family connections. It’s a nice way to cook cabbage and to feel connected to my roots. I didn’t ever imagine having a conversation about cabbage would bring me close to tears.

Now I understand why you’re so moved. It’s a way to travel across time and using cooking as a method to tap into history and memories.

Exactly. When I was mentioning it to my husband Ed, I said, ‘What if we made it with lamb and used Uzbek spices?’. It would completely transform the dish and take us further east. But it’s the same concept, right? Just a different meat and a different set of spices. The dish has potential to travel, and maybe something like this exists in Uzbekistan or Turkmenistan, because everybody’s got cabbage and everybody’s got rice.

Especially during lockdown when we couldn’t travel and for me now, I’m more into learning everything I can about regional Chinese food. The reality of travelling China is still very hard - I don’t have years that I could just take off - so food has been one way to make myself learn and travel with the taste buds.

Who will you invite to eat your kalam polo? And how will you serve it?

I’ll invite you to come! I’ve only ever made it for my family but I think this could be a really lovely dinner party dish. On the Iranian table you will always find a sabzi khordan platter of herbs. Some crunchy vegetables - cucumber, radish, kohlrabi, some cheese; feta or a good Turkish soft cheese. It comes out at the beginning of a meal and it’ll stay on the table throughout the course of the meal.

Interestingly, the only feedback I’ve had from diners at the supper clubs was that I could do away with that salad platter. But I can’t serve you an Iranian meal with that platter being present. It’s what you would use to break up the richness. Instead of having just rice, you want a little crunch and rawness. Iranian pickles are just vinegar pickles, but they're so good.

That raw salad platter is very Southeast Asian.

I’m interested in this because I think so much of eating new cuisines is not just about the openness you need to try new food; it’s learning how to eat it, and obviously the best way to do that is to eat with people who know how to eat it. But my bugbear is when people treat me like, Oh I want you to take me to eat Chinese food but you’re going to educate all of us. I end up being the person doing the ordering, translating, standing up pouring tea and serving people. It’s like , can I eat now?

My other bugbear is when people don’t understand the rules of balance in ordering a nice balanced meal, so you don’t order every single spicy thing and then go home complaining how it was so spicy and full of MSG. But you didn’t order soup, or vegetables, or rice!

I remember on Samin Nosrat’s show Salt Fat Acid Heat where she talks about going to a friend’s Thanksgiving table as a kid and being like, I don’t understand why everything tastes the same. It’s all savoury and yummy, but where’s the pickle? Where’s the sweet? The only thing I really liked on the American Thanksgiving table was the cranberry sauce, because it gave it a little bit of acid. So with the sabzi platter I need to explain what it’s for and how how it stays on the table because maybe some of the diners thought it was a cold appetiser.

Certainly there’s an etiquette that needs to be understood in many cuisines; someone in my family cuts their spaghetti with a fork. I wonder what the waiters do when they go to Italy and look over and see a fork and knife cutting spaghetti!

It’s the same with chopstick etiquette. But if you don’t know, you don’t know! That’s why it’s important to have good companions with you.

So tell me about your cookbook.

It traces the flavours and foods from Turkey to China, focusing on different preparations and ingredients. The book is divided like a normal cookbook according to soups, rice, meat, wrapped foods like dumplings and dolma, dairy and preserved foods, pickled fermented things. For each of the chapters I also include a historical, academic and personal essay. One that I’ve just finished is the introductory essay about the cultivation of melons, and the homeland of this fruit being in Central Asia - the mountains of the world - and how they’ve spread across the world. I tie that together with my father travelling to Uzbekistan in the Soviet times and trying to bring a melon back to the US because it was the best melon he’d tasted in his life that he wanted my sister and brother to taste, and it getting thrown in the bin by customs agents. I wasn’t even born when it happened but this melon plays a really strong imagined taste memory in our family.

The book is about how we travel and move with food, both imagined and real. Melons were spread to Spain from the Arab traders going into Andalusia, which is why you’ve got really great melons in Spain because they’re direct descendants of the ones from Central Asia - versus the ones that came via Romans through Turkey and lost their deliciousness somewhat.

Like a genetic connection.

Yes, it’s how you care so much about something that you want to take it with you, whether that be for commercial or survival purposes - like dried yoghurts that you take on camel treks across the Gobi. There is this fermented dairy product, a hard little ball which - when you add water - liquefies and nourishes you on these long trips.

I’m really excited to read your book when it comes out. Best of luck, Anna!